Hi there! It’s been a while. I’ve been kept busy by all my university work…and this shawl.

The shawl is knitted to celebrate the wedding of my friend (now friends, I should say). A wedding is really the perfect excuse for all the heritage crafts and heirloom projects that might seem too serious to gift in other occasions. I did ask the recipient beforehand if she would like it, though, and I was so, so honoured that I got an enthusiastic ‘yes’. I’m sure this sentiment is shared by many makers, whatever gift they are making.

Shetland fine openwork, a knitted lace, seems to have emerged with the beginning of the reign of Queen Victoria, who championed and popularised the craft. It was probably spread from the Isle of Unst to other parts of Shetland. What surprised me the most when I first read about it was that Shetland shawls and other lace pieces were largely exported as luxury items and rarely worn by islanders themselves. Women bought yarn from spinners and knitted mostly in their homes. They then took them to local merchants and exchange the finished objects for goods or (commonly after the 1880s) money to supplement the household income. The ‘supplement’ nature of this work probably means it was not compensated as much as a job outside the home would be for the same hours and skills. Besides, it was not always easy to spin an even 1-ply yarn at 1600 metres per 100 grams. For a piece of knitting with a large ‘plain’ area (i.e. only knit stitches), the unevenness was impossible to hide but could only be discovered after the area was worked. Then the maker had to either frog (unravel) the area or continue with the risk of the whole piece not being able to sell.

Whilst it is very reasonable to point out that Shetland ladies did not usually wear this type of lace (I’ve been to the Scottish Highlands once, in summer, and it was not fine lace weather), I imagine that at least for some, it wasn’t just about making money. Some sort of fulfilment must have been from the satisfaction of having a piece ‘properly done’ by continuing and adapting a traditional pattern, technique or material. I think this sort of satisfaction is also why many modern knitters are willing to spend hundreds of hours on lacework.

Intricate handknitted lace items can still be bought today (a quick search on Etsy would show many are form eastern European countries with a long and prominent craft tradition), but many are knitted for friends or family members. It always makes me so happy to see people share the gifts they have made, whether big or small, simple or complex. I joke with my online craft friends that no handmade fibre project can claim to be so unless they have a hair or two woven into it. It is the proof of existence for the maker, who tries to go against the irregular nature of handicrafts and, at the same time, accepts it. It is about wrapping up hours, weeks or months in one’s life, along with the songs they have listened to and the perfume they have worn and the memories they have made, and putting it squarely in someone else’s hands and saying: ‘All this, for you.’

A Wedding Shawl

I have not read anything about there being a standard form of ‘wedding shawl’ in the Shetland tradition. However, there is definitely a category of square shawls with similar sizes and a few construction methods. The samples I’ve seen mostly measure 1.5-2m on one side and have three parts: a central panel, four borders and a strip of edging. It is worked flat in garter lace from centre out.

Neither is there a standardised yarn weight. A widely available yarn is the Shetland Supreme Lace Weight 1-ply by Jamieson and Smith, which weighs at 400m/25g. The Queen Ring Shawl examined by Sharon Miller used a yarn at 700m/25g. From my experience, if you want the shawl to be a true ring shawl (i.e. you want to be able to pull the shawl through a ring) at the size of the Queen Ring Shawl (210cm on the side), go for 700m/25g or finer.

I chose a rectangular shawl because I had very limited time, but I did enlarge it because for me, an abundance of fabric does mean an abundance of cozy happiness.

Pattern

Shell Grid and Spider Webs Puzzle, pattern no.19 in the book Shetland Knitting Lace by Toshiyuki Shimada.

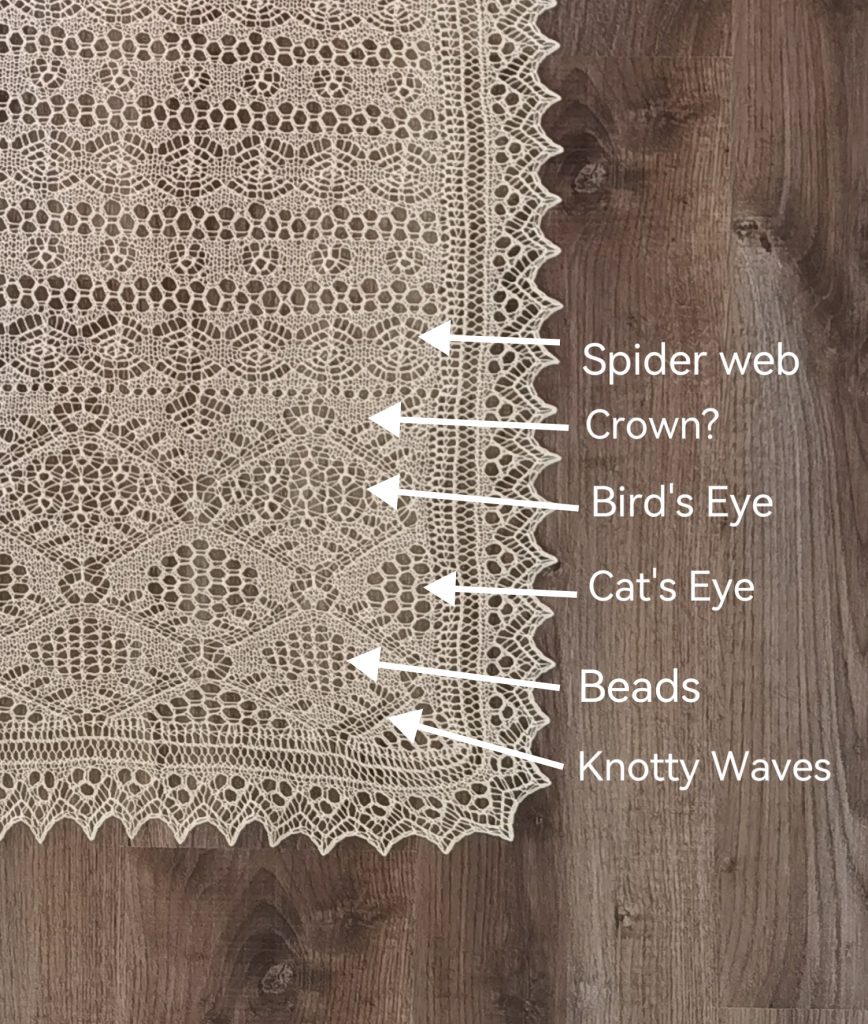

The names of the motifs are confusing. One motif (or two highly similar motifs) might just have two different names if they are produced in two different regions. Names do not mean everything, but I’ve had fun trying to match the motifs with names according to this article by Carol Christiansen at the Shetland Museum (https://www.shetlandmuseumandarchives.org.uk/blog/whats-in-a-name)

The double yarnovers (YO’s) in the diamonds were called Cat’s Eye, but perhaps the ’Spider Web’ in the pattern name is referring to the three rows of double YO’s in the centre panel. It has a really simple but effected edging.

Yarn

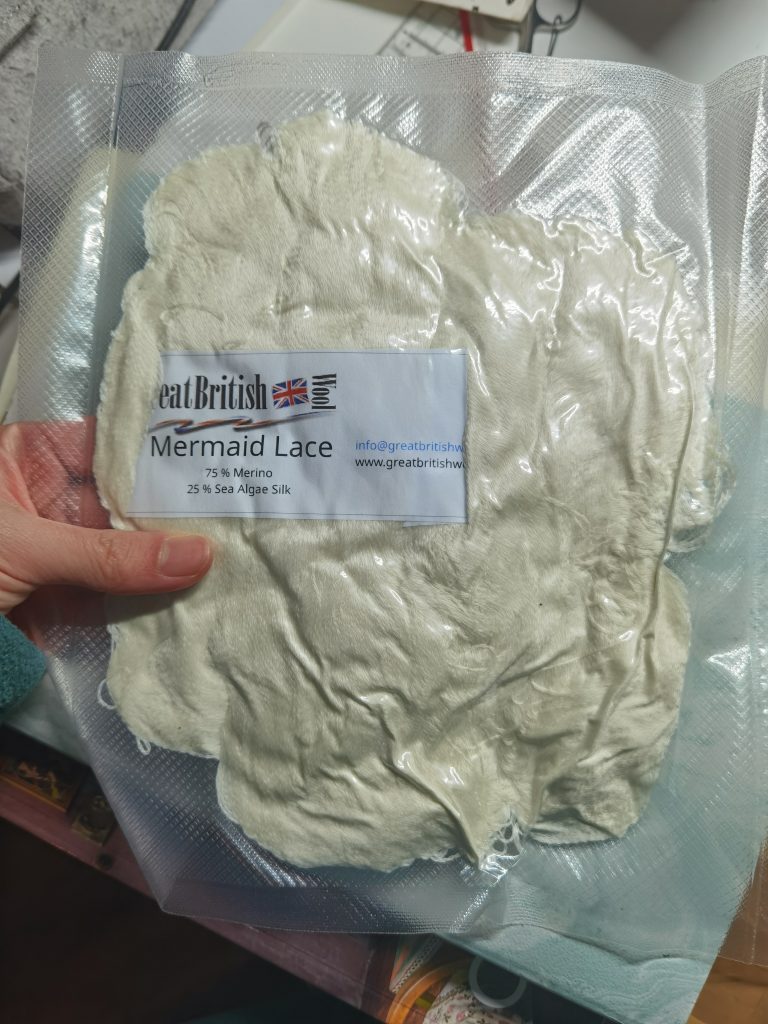

Mermaid Lace, in colourway #naturel, sold by Great British Wool in the Netherlands. This yarn is 75% merino and 25% sea algae silk. ‘Sea algae silk’ seems to be a semi-synthetic plant fibre like viscose, with algae involved as part of the raw material. (At this price point I don’t think it has anything to do with sea silk, which is fibre produced by actual shells.) The brand name for the most popular product of its type is probably Seacell.

I bought the yarn, because I had never worked with this fibre before and was curious. What I like: it was a little cheaper than a wool/silk blend and has blocked very well. The whole skein was continuous so I didn’t have to deal with a single yarn joint. What I do not like: it lacks the sheen and smoothness of real silk and doesn’t feel as strong, although it doesn’t shed. In conclusion, I’d rather use a traditional Shetland 1-ply or another natural fibre yarn.

It’s also worth mentioning that whilst I prefer to support small businesses, it was disappointing to have received a 93-gram skein when I had ordered 100 grams. It was one of those days between Christmas and the New Year and I somehow did not contact the customer service, but I really should have.

Needle

2.5mm 80cm circular needles. See modification below.

Modification

This Japanese knitting book follows Japanese sizing for knitting needles. The suggested size was no. 1=2.4mm. I figured that I could use a 2.5mm since I knitted on the tighter side, and in any case it was probably okay to make the lacework a little more open by going up a needle size.

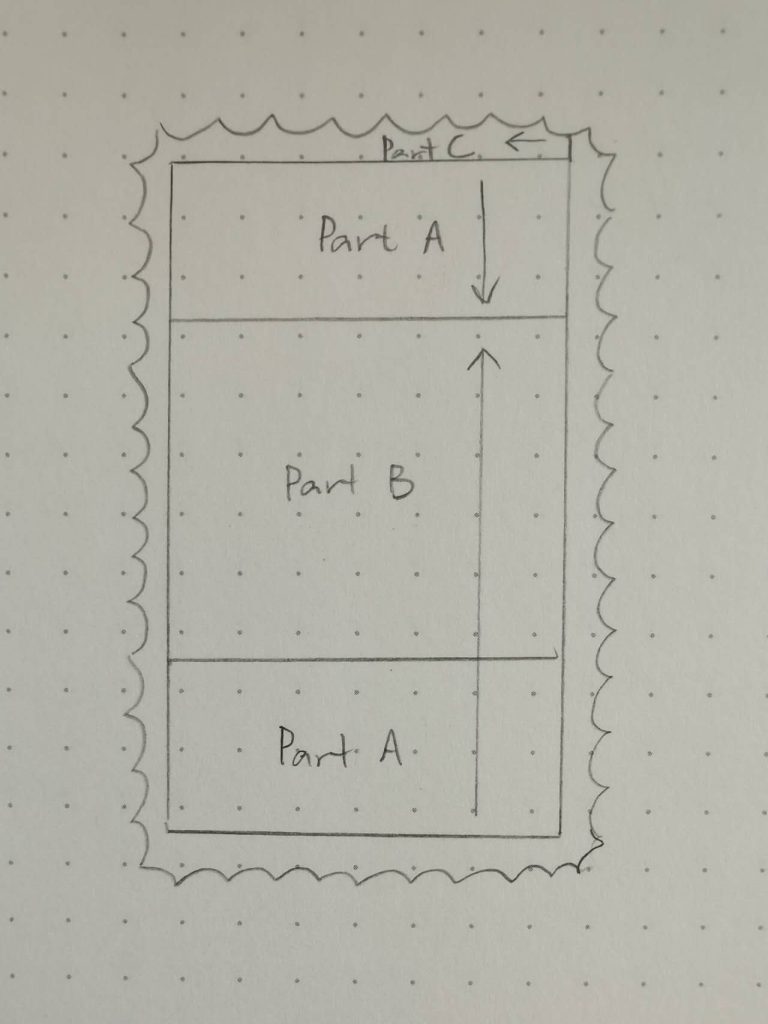

I am not going to give out the pattern, but it is probably necessary to explain the structure of this shawl. The centre is knitted first, and then an edging is knitted onto it by picking up either live stitches or the vertical edge of the centre as you go (see schematic below). The four ‘corners’ of the edging have short-row shaping to help it lay flat. I know that traditionally people can achieve this by other methods, but I haven’t tried any of those yet.

I enlarged the pattern by increasing both the width and the length. I casted on 133 stitches instead of 101 for the centre panel and knitted Part B 8.5 times instead of 5.5. The spider web pattern in Part B requires the stitch count to be (something dividable by four) plus two, so I made one central increase before the spider web to get 134 and a central decrease after it to get it back to 133. Due to the openness of the lace, the change of one stitch is not visible.

The enlargement meant I had to recalculate the edging as well, because the number of stitches available for pick-up changed. Originally, at each corner you do two repeats with four short-row shaping each. I did 1.5 repeats following the original placement of short-row shaping in order to make the total number of repeats fit the number of edge stitches on the centre panel.

The pattern says to Kitchener-stitch the last row of the edging to the provisional cast-on. It just didn’t make sense because that would be two rows too much (the Kitchener stitch row plus the provisional cast-on row). To make the number perfectly fit, I knitted only ten rows of the last repeat (there were usually twelve in each repeat). Then I Kitchener-stitched the end to the provisional cast-on, following the lace pattern. I am quite proud of this solution because it is completely invisible.

Somewhere in the pattern it said to purl (looking from the right side). It seemed strange because the rest of the lace was entirely garter. I knitted those stitches and so far I haven’t sensed a ‘mistake’.

The pattern originally calls for 45 grams of yarn. I estimated (based on the increase of stitches in the centre panel) to need about 80 grams. I ended up using 86 grams. Besides the inaccuracies in my estimation, it was probably also because I knitted much more loosely than expected as it was difficult to tension the yarn tightly at such a weight. Like I’ve point out in the Yarn section above, I was lucky not to have needed more than 93 grams.

The original finished size is 53*118cm. I ended up with approximately 70*170cm.

Conclusion

This shawl took about three months of my craft time i.e. one full day every week for three months and many mornings before I had to leave for university. Knitting outside my room just didn’t work because I was a) engaged in some other activities that made it difficult to steady my hands, and b) worried about putting a white shawl on any public surface.

The pattern itself is relatively straightforward. The first difficulty was, of course, to understand the instruction written in Japanese. Google translate was horrible so I had to rely on my knitting experience. Fortunately, much of the text description was also found in graphs and charts. Then I had to get my hands used to the tiny yarn. After that, it was only fiddly when I did the edging, because I had to turn about every twelve stitches, and by that time I was handling a giant cloud of stitches on my lap. It did give me a lot of time to go over my favourite documentaries and films, and the last bit of edging was surprisingly quick!

Traditionally, Shetland shawls could be sent back to the maker for maintenance. I think it only fair for me to offer that too because I don’t want a gift to become a trouble (same as how you do not use non-machine-washable yarn for baby knits).

In general, I am very pleased with this shawl. It does pass the ring test, despite not being a traditional wedding shawl size or thickness. I do have a whole lot of actual Shetland 1-ply in my stash, so I am really犀利士5mg looking forward to taking my Queen Ring Shawl project out of hibernation in the near future.

Reference used for Introduction

Christiansen, Carol. Shetland fine lace knitting: Recreating patterns from the past. Marlborough: Crowood, 2024.

Mann, Joanna. ‘Knitting the Archive: Shetland Lace and Ecologies of Skilled Practice’. Cultural Geographies 25, no. 1 (January 28, 2017): 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474016688911.

Leave a Reply