This is an exhibition review I wrote back in early 2023. Despite having never been published, it was actually what prompted me to make this blog, so at last I am sharing it with you! The exhibition ended in 2023, but I highly recommend the catalogue (available in French) if you are interested in the subject. Let me know if I have a mistake with terminology, etc. All pictures are mine.

Display of coats from ikat fabric.

Stepping into the dimly-lit exhibition hall at the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA) in Paris, visitors to On the roads to Samarkand: wonders of silk and gold are transported to the steppes of Central Asia of more than a century ago. The exhibition is curated by Yaffa Assouline, who has written three books on Uzbek arts and crafts in the past three years. Assouline and the curatorial team at IMA have worked in collaboration with the Art and Culture Development Foundation of the Republic of Uzbekistan to bring to Paris more than three hundred works of Uzbekistan textile art from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most of which are displayed for the first time outside the nation’s state museums, painting individual and societal identities with their threads of gold and silk.

The Transoxiana region, which encompasses the whole of present-day Uzbekistan, is situated at the crossroads of civilisations along the Silk Roads. Over time, the nomadic tribes as well as the residents in major trading cities such as Samarkand and Bukhara developed their unique artistic styles. Textiles were made and decorated using cotton and silk produced in the oases and wool from the steppes and mountains. In the nineteenth century, traditional textile arts were promoted by the government to unite the newly formed Emirate of Bukhara under one identity. A Russian protectorate since 1868, the area saw an increase in the production of raw materials for textile-making, and various types of textiles became increasingly ornamented until the decline of traditional crafts in the soviet era. The exhibition corresponds to the global resurgence of interests in textile arts. Additionally, the interest in Uzbek culture is almost certainly related to the increasing political engagement of France in Central Asia. The exhibition opened the day after the president of Uzbekistan visited Paris and coincides with another exhibition, The Splendours of Uzbekistan’s Oases, at the Louvre Museum.

The exhibition spans more than 1,100m2, divided between two storeys. A diverse range of topics are presented along an approximate pathway: chapans (coats) for men of high status, horse-riding gear, suzanis (embroidered fabrics for decoration), carpets, coats made with ikat fabric, jewelry, tribal costumes and Uzbek avant-garde paintings. Hence, the exhibition mainly presents textiles whilst being supported by objects of metalwork and paintings. The intended spaces of the artefacts varied from the exclusively male space of the court to the domestic space associated with female needlework to the steppes where nomadic tribes lived. The diversity of the topics reflects the richness of Uzbek cultures as well as a shared appreciation for textiles to display creativity and convey identities across varied living circumstances.

The lavishness of the chapans sets the mood of excitement from the beginning of the visit. These kaftans are almost fully covered in zardozi, a type of gold embroidery, in various regional styles. Nearby, embroidered caps were suspended upside-down from the ceiling and lit from the inside, as if they were decorated lanterns floating in an otherworldly space. The focused lighting in the dark halls brings out the shimmer of the gold and the bright colours of the silks, recreating a distant and opulent world where power was visualised by the amount of gold used on garments.

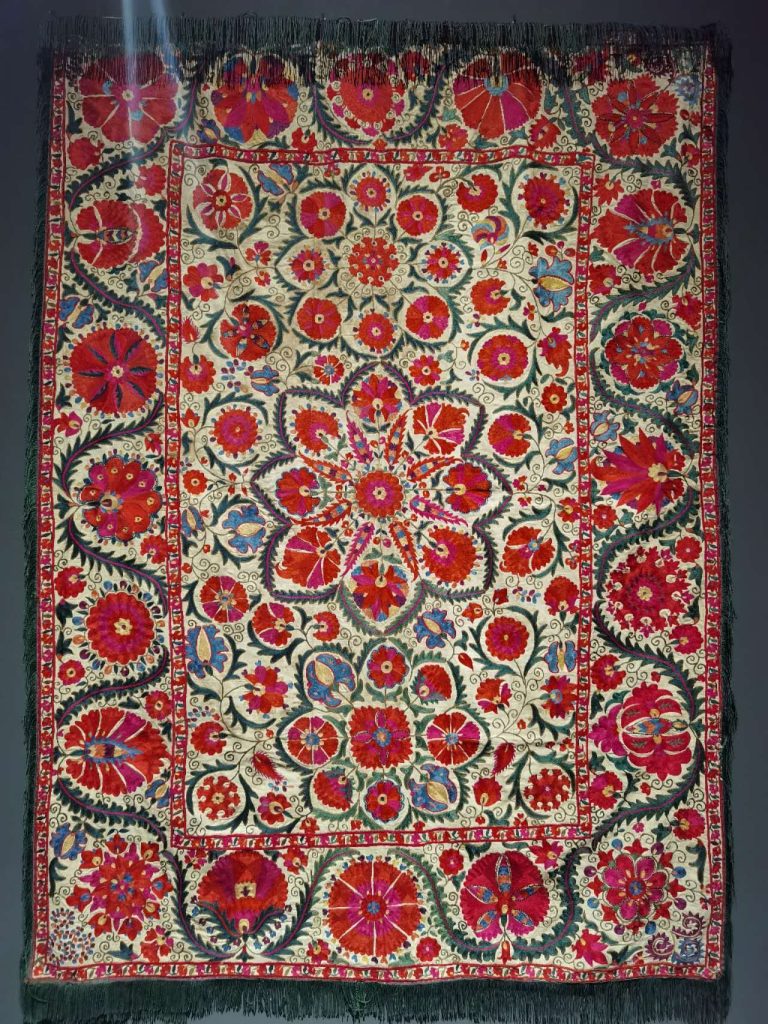

Some other objects were made in ordinary homes but have no less social significance as representations of individual identities. The suzanis were embroidered by women, who were forbidden to use gold, as dowries for the daughters of the family. Displayed without cases, every stitch and seam are visible, contrasting with the sheer sizes of these works and testifying to the entire family’s effort to stitch an image of patience, taste and creativity for the future bride. In addition to being a testament to the women’s skill and ingenuity, kiymeshek, a headdress worn by the Karakalpak women, distinguishes her marital status and rank in the family by colour and embroidery motif.

The curators have made many efforts to help the audience connect the artefacts with the lives of real people. With the exception of the pieces of jewelry and a few chapans, items can be observed closely without a glass barrier. Many garments are displayed on pedestals which the audience may walk around to appreciate the three-dimensional design details that allow garments to be worn on a moving body. The corridor connecting the two storeys is lined with photographs from the early twentieth century of women wearing traditional gowns and jewelry. A film accompanies the group of ikat coats, which demonstrates the long time and intense labour required for raw silk to be dyed and woven into patterns.

Despite the large exhibition spaces, the sheer number of objects means that elaborately decorated pieces are often placed close to each other, creating an immense sense of splendour. Perhaps it is intended that the audience feels overwhelmed, as the exact goal of many of these items was to impress the viewer, whether it is to convey the power of the emir and the high officials or the desirable qualities of a future bride. Besides, bright colours and intricate patterns were likely layered on top of each other when they were used in real life. On a more practical note, there is only one bench near the exit of the first storey. An exhibition on such a grand scale would benefit from more seating areas for the audience to rest their feet and their eyes.

The exhibition ends with a group of twenty Uzbek avant-garde paintings from the 1910s to the 1930s, many of which depict traditional textiles and therefore symbolise a connection between tradition and modernity. Still, it seems abrupt to introduce a new medium, painting, which has not been mentioned in the rest of the exhibition. All but the last section of the exhibition amaze the audience with intricate patterns which required intense labour and were powerful symbols of identities; the hasty discussion of modernist tendencies brings the audience out of this sophisticated world without a conclusive comment on these traditional crafts.

With its wide range of artworks and artefacts, this immersive exhibition is well worth a visit, especially for those interested in textile arts and in Central Asian cultures. Made mostly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the artworks are from a time when the idea of a nation was forming on the current land of Uzbekistan. On the one hand, they attest to the power of textiles and traditional arts to create a sense of belonging for people. On the other hand, the diversity of the stories they tell signifies the vastly different lives people had. Through the grand scale of the exhibition and the multiple techniques of display, the curators convey the pride of Uzbekistan in the richness of its cultures.

On the roads to Samarkand: wonders of silk and gold ran from 23 November, 2022 to 4 June, 2023.

A chapan coat with gold embroidery.

An example of suzani embroidery. It was displayed as a wall hanging, but I wonder if it could be used in other ways.

Another example of suzani. They are stunning!

Bibliography

Aslan, Chris. Unravelling the Silk Road: Travels and Textiles in Central Asia. London: Icon Books, 2023.

Khashimov, Mukhiddin. ‘Uzbekistan-France: A Comprehensive High-Level Partnership’. The Diplomatic Insight, November 1, 2023. https://thediplomaticinsight.com/uzbekistan-france-a-comprehensive-high-level-partnership/.

Pommereau, Claude, ed. On the Roads to Samarkand. Wonders of Silk and Gold. Paris: Institut du Monde Arabe, 2022. Published following the exhibition On the roads to Samarkand: wonders of silk and gold at the Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris.

Leave a Reply